War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for (Justice) Truths and Rights is a multimedia exploration of collective resistance, activism and organization by Black communities in the UK. Through video installation, photography, painting, archival documents and cutting edge 3D technology, we are invited to embark on a visceral journey of the Black British experience, and responses to decades of institutional racism and state-sanctioned violence faced by Carribean migrants, since the first arrivals entered Britain in the 1940s and 50s.

We start at a chronology of Caribbean migration to the UK (known as the Windrush era) through the numerous legislative powers, including ‘sus’ laws (as we know now as ‘stop and search’ – soon to be granted more power by the authoritarian Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill) the Colour Bar and Race Relations Act of 1965, to the uprisings of Brixton, Toxeth, Chapeltown and Handsworth in the 1980s. We arrive in Tottenham, the focal point of the show, where in 2011, the North London town re-emerged as a frontline of resistance following the murder of Mark Duggan. Upstairs, the show dedicates the space to Duggan’s inquest via a groundbreaking display by Forensic Architecture – a multidisciplinary research group based at Goldsmiths, University of London that uses architectural techniques and technologies to investigate cases of state violence and violations of human rights around the world. Here we are presented with a digital reconstruction of the shooting, showcasing vital evidence to the campaign.

The exhibition is essential viewing – an impactful, inspirational and invaluable resource to generate awareness and action. We spoke to co-curators Rianna Jade Parker, Kamara Scott and designer Abi Wright about the urgency of the show ‘post-pandemic’, working with large scale art institutions, access to archival materials, youth, leadership and the legacy of the exhibition.

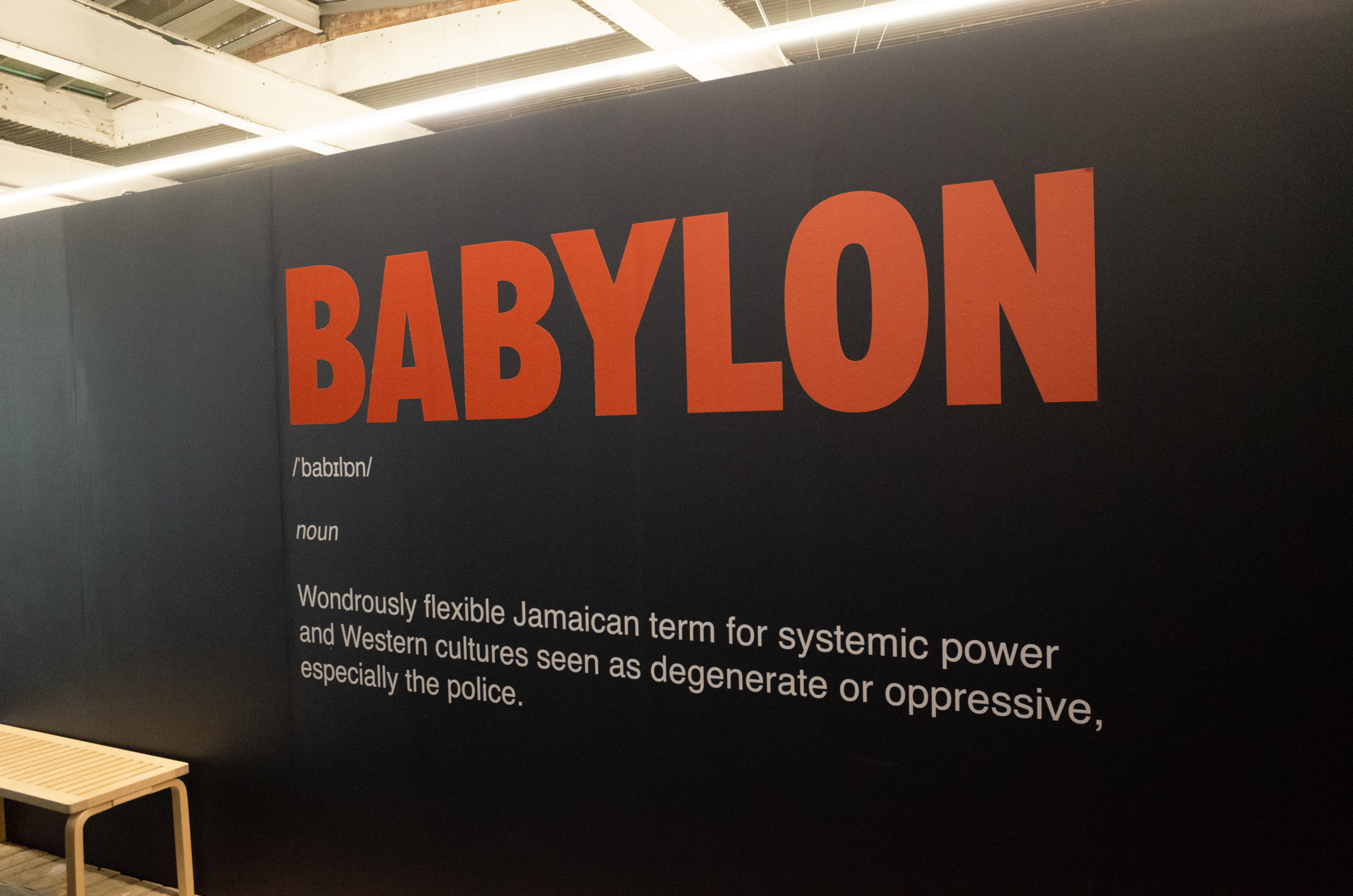

As we enter, we find Rianna and Abi at the latrine, a large orange modular construction, housing pamphlets, leaflets, books, newspaper cuttings and various artefacts of resistance from the 1970s-1990s. Central to the exhibition, Abi explains it was a ‘complete project in itself’, as she explains some of the design challenges the team faced from conception to installation. ‘The whole exhibition is about detail,’ she continues, and with such a wealth of sensitive material, it has been paramount to ensure information has been presented in the most respectful way – ‘giving everything the space it needs to do it justice’. However, the show’s title substitutes the concept of ‘justice’ for the more appropriate terms ‘truths and rights’ – a clear indication that a possibility of ‘justice’ in its widest definition is a myth to the Black community, ‘inna Babylon’.

On opening night, Rianna was ‘barefoot and in house clothes’ at 6.30pm as visitors from Tottenham Rights flooded in, rushing and rejigging around to make everything cohesive. She admits that she visits the space everyday, to make sure everything is going to plan. This extensive labour is an apparent requirement of independent curators – and particularly those of colour working with large scale institutions – to ensure the message and narrative of their work is conveyed precisely and authentically.

Tottenham Rights was founded by co-curator Kamara Scott and her father, Stafford Scott, formally launched in 2012. The group is an extension of the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign founded by Stafford following the mass arrest of 369 people during the Broadwater Farm Estate disturbances in 1985. “My dad’s been campaigning since he was 21 – he’s 61 now and I’m 27. We have to bridge a gap and learn how to communicate. We now have to decide how we go forward, because evidently throughout the exhibition you can see as there have been campaigns, and they’ve worked the best they can – but it takes an army.” The main focus for Tottenham Rights now is their work on dismantling the Gang Matrix – “to get names taken off that – and the Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill – that comes down to numbers and those happy to join the campaign.”

In June 2020, Kamara’s uncle Millard Scott, was violently tasered during a police raid. The 62 year old collapsed down a flight of stairs, and the bodycam footage of the attack was brought to public attention (as Millard Scott happens to be the father of rapper Wretch 32.) Wretch has been amplifying the exhibition on his social media, and his outreach has evidently worked as we meet Malik, a 22 year old Saxophonist and producer from Forest Hill who saw the show advertised on Wretch’s gram. Malik, of Jamaican heritage, says that he ‘didn’t know what he was coming into’ as he arrived at the exhibition, but was pleased to see representation of his area – “I’m from these places man…I see Bricky on the wall”. “The pain and experience of our ancestors – it’s interesting that sometimes you don’t understand the extent of what they went through,” he continues. “It’s sad to see but interesting how we’ve been treated in this country, even to this day.” He recommends the show, “I’ll tell everyone to come here! I’m a creative myself so it’s good to see things that will inspire me in other ways.”

The show is nothing short of inspirational in the face of overwhelming adversity – both in content and fruition. The struggle faced by community groups and activists is parallel to the unrelenting energy of Rianna in her pursuit to document these histories of Black Britons accurately – her experiences delving into catalogues from the Yorkshire Film Archive who were incredibly helpful, to the BBC who Rianna explains “were being stingy – and the Police, as you’d expect – very stingy’. She has over 12 hours of podcast material with her conversations with Stafford over a bottle of rum, – “we had Appleton and it was all over!”

A 9-screen video installation, another monument of the exhibition, uses footage donated by a pioneer of Black British film, the late Menelik Shabazz, and Rianna is eternally grateful for his generosity and support of the show. “He gave us the master files to all of his work with no inhibition and said do what you need to do. No one else was like that, even with some of the photography, the egos were incredible!” Ego and identity politics have been recurrent barriers in organising, in addition to generational differences. “I don’t respect a lot of people or their politics – but young people – I have nuff time for.” she states. Young people are Rianna’s passion, her rollout of a Learning and Development programme that will run alongside the show is of the highest priority and importance, as she reflects on the decay of government investment in future generations – “Youth work was a respected, regulated thing – it was required before the Tories got rid of it as a sector.”

The collective power of young people was actualised on the Broadwater Farm Estate, and serves as a model for mutual aid and community power. The ingenuity and DIY ethic of the estate’s inhabitants was a force to be reckoned with as they reclaimed an abandoned chip shop. “They were policing themselves – The Young Mothers Group, The Co-op – they did it themselves, but the 80s was the 80s and Thatcher had a very particular agenda.” This agenda has been reaffirmed by the current Conservative government, whose hostile environment, underpinned by racism, fear-mongering, austerity, surveillance and lies has meant that much of the agonizing content of the exhibition remains intact if not inflated, repackaged under new laws and systems.

“As soon as July 2020 hit, everyone gave a shit,” Rianna remarks, as a world ravaged by Corona virus suddenly turned attention to injustice – from police brutality to under representation. Visibility to the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement took hold – sparking mass protests and calls for revolution from the top down. Since then, we have witnessed both virtue signalling – from swathes of black squares, declarations of Diversity and Inclusion drives and meaningless statements to an impetus for genuine change. On the future of organising, “The advice is to stick to grassroots.” Kamara believes. “You have to get out of your house, talk to your neighbour, say are ok? Be accountable for each other and you have to commit to that. You have to sacrifice something in order to do that. You have to let something go in order to gain that level of accountability from your peers. That’s it.”

In this collaborative effort, there have been numerous sacrifices to achieve wider goals. Rianna has been outspoken and a revered voice in the world of Black art in the UK – since her graduation from Goldsmiths with an MA in Contemporary Art Theory, she has carved a career as revered curator, writer and cultural critic. Her unshakeable values are at the core of her output and as the contributing editor at Frieze Magazine – her former role as producer at Tate Collective, shows at South London Gallery, Iniva, Southbank Centre and the RCA she has a body of work that seeks to find truths and rights through the artistic landscape – past, present and future.

War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for (Justice) Truths and Rights is at the ICA, London until September 26th. £5 / Free on Tuesdays

Those from the Black community can contact Tottenham Rights for a free ticket.